You know that moment when you finish speaking, and you feel a little unsure—like you said many things, but you’re not sure what actually landed?

You had content. You had good intentions. You even had slides. But your talk still felt like a long hallway with no doors, and your listeners didn’t know where to stop, what to hold, and what to do next.

That’s not a confidence problem.

That’s a structure problem.

The Monday meeting I still remember

A plant manager once walked into a Monday meeting with solid data and a clean deck. He wasn’t performing. He was leading. You could tell he cared about the company because he talked like someone who had been carrying the weight of results for years.

The presentation was “good,” in the academic sense. Charts were clear. Recommendations were reasonable. The problem was not the content—it was the experience of listening. The audience received the talk like a report that needed translation, interpretation, then repackaging by managers, then again by supervisors.

Afterwards, I noticed something that stayed with me.

Nobody argued with him. Nobody challenged him. Nobody even looked angry.

They simply looked… unchanged.

The quiet question people don’t say out loud

When people listen politely, it usually means one of two things: they’re either convinced, or they’re lost. And in many organizations, polite listening is confusion dressed as respect. People don’t want to look slow, so they keep their faces neutral and their questions inside.

Under that silence is one question that keeps pulsing:

“Okay. So what do we do now?”

If your talk doesn’t answer that, people will treat it like information—not instruction.

The next week, he shifted one thing

Same manager. Same topic. Same urgency. But this time he didn’t open with the data. He opened with a short scene—one shift, one delay, one rework, one real moment that made the problem feel human before it became analytical.

Then he did something even more important: he made the path visible. He showed where we are, why it matters, and what decision we’re making. The deck still supported the talk, but the talk now had a spine.

That’s when the room changed. People didn’t just nod. They started asking action questions—the kind that mean, “Sige, paano natin sisimulan?”

That shift didn’t come from charisma.

It came from storyboarding.

If this feels familiar, it’s not just you

If you’ve been presenting for years and people still “get it” but don’t move, that’s often a culture pattern. People present updates, but decisions don’t travel. Meetings get longer. Alignment gets weaker. Everyone works harder just to stay confused.

If you want to fix that as a team—not just as an individual—this is the kind of skill worth building inside the organization. I run practical sessions for leaders and teams who want clearer updates, stronger proposals, and meetings that end with action—not interpretation.

If your organization is exploring that, you can reach me at leadership@jefmenguin.com.

Why storyboarding works

Most speakers think they need more content. What they really need is a clearer route. Storyboarding forces you to choose the “spine” of your talk so the audience doesn’t have to build it themselves while you speak.

When the spine is clear, your confidence rises too. You stop guessing whether people are following. You can feel it, because their faces change. Their questions change. Their energy changes.

And storyboarding protects you from one thing that hits good leaders the most: rambling caused by care. When you care deeply, you want to explain everything. The storyboard doesn’t kill your passion—it gives your passion a container.

The Slide-Deck Trap

Let’s name the enemy: The Slide-Deck Trap.

This happens when your slides become your structure, so your talk turns into “next slide, next slide, next slide.” The problem is that slides are fragments. Your audience needs a journey.

If the deck is the driver, you may sound organized, but people still won’t feel guided. They’ll remember details, but they won’t remember direction.

Use this in 5 minutes (even if your meeting starts soon)

If you have a meeting in 30 minutes, don’t open PowerPoint yet.

Get a sheet of paper. Draw nine boxes. Fill only the first three. Practice those three out loud in 60 seconds.

When your opening has shape, people stay with you. Everything else becomes easier.

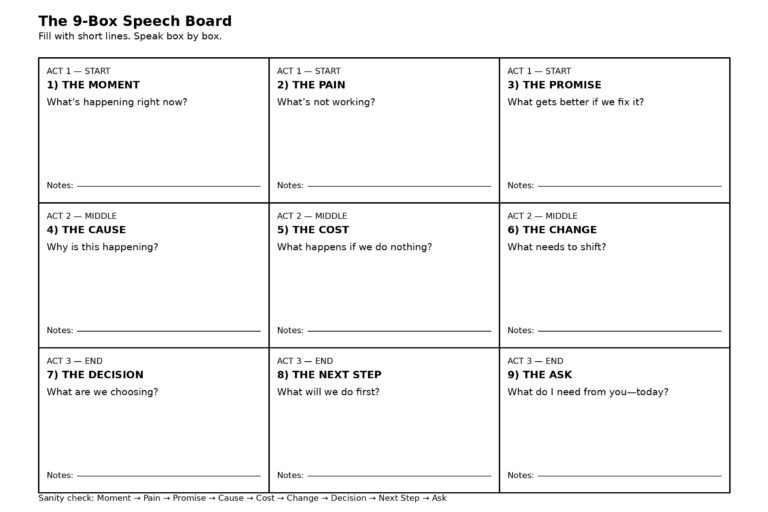

Print this: The 9-Box Speech Board

Draw 9 boxes (3 rows × 3 columns). Don’t write essays inside. Write short lines.

Then speak it box by box.

Copy-paste template

Speaker sanity check

Read the nine boxes in one breath and check if it flows:

Moment → Pain → Promise → Cause → Cost → Change → Decision → Next Step → Ask

If any box feels fuzzy, that’s usually where your audience will get lost too.

A quick example (operations)

Topic: reducing errors in processing.

Moment: “Last week we had 12 reworks.” Pain: “It’s draining time and energy.” Promise: “We can cut rework in half in 30 days.”

Cause: “Most errors happen during handoff.” Cost: “Delays, overtime, customer complaints.” Change: “We need one clean checklist at handoff.”

Decision: “We standardize the handoff checklist starting Monday.” Next step: “Today we test it on Line 2 for one shift.” Ask: “I need two volunteers to co-own the checklist update.”

Notice how it ends. Not with appreciation. With movement.

Two more mini-examples (so you can adapt fast)

1) HR announcing a new policy

Moment: “Starting next month, we’re changing the performance process.” Pain: “Right now, feedback is inconsistent, and people feel surprised.” Promise: “This new system gives clarity and fairness.”

Decision: “We’re rolling it out in three phases.” Next step: “This week, managers will attend a 45-minute briefing.” Ask: “I need you to bring two real cases we can use for practice.”

2) Sales proposal to a client

Moment: “You want faster turnaround without sacrificing quality.” Pain: “Your current process creates delays and rework.” Promise: “We can cut turnaround time by 30% in 60 days.”

Decision: “We’ll start with a pilot project.” Next step: “Kickoff call on Tuesday with your ops lead.” Ask: “I need one point person from your side for approvals.”

Different situations. Same storyboard.

Three common mistakes (so you don’t waste the tool)

Mistake #1: You write paragraphs inside the boxes. The point is clarity, not completeness. Short lines force you to choose what matters.

Mistake #2: Your ending has no decision. If Box 7 is vague, your audience will leave with “nice idea” energy and no action.

Mistake #3: Your ask is soft. “Support this” is not an ask. An ask has a name, a role, and a deadline. Di ba?

Share this with your team (copy-paste message)

If you want this to spread inside your organization, don’t just forward the article. Send a specific invite.

Here’s a message you can copy:

Team, before we build slides for next week, let’s storyboard first. Use the 9-box speech board and bring your paper draft to our prep meeting. We’ll tighten the spine together so the presentation ends with a clear decision and next step.

That’s how this becomes culture, not just personal improvement.

The shift to try today

Don’t outline your talk as bullet points.

Storyboard it as a journey—where we are, why it matters, what we’ll do next.

When your talk has a journey, your audience doesn’t just listen.

They arrive.

Your 24-hour push

Before your next meeting or presentation, don’t open PowerPoint first. Open paper.

Draw the 9 boxes. Fill only the first row. Then speak that row out loud in 60 seconds.

If your opening has shape, the rest of your message gets traction.

If your talk has no journey, people won’t arrive.

If your team is stuck in meetings, misalignment, or slow decisions…

Let’s design one shift they can use immediately.

→ Shift Experiences